Selecting the appropriate playing area size for your players can be tricky, but using a straightforward mathematical formula can help you create practices that achieve the desired technical, tactical, physical and psychological results.

What is relative playing area?

Relative Playing Area (RPA) is a calculation that measures the average amount of space available per player in a practice. It’s determined by dividing the total area of the playing space by the number of players involved. This will then give you three categories of that area size large, medium or small.

Using RPA when designing your practices helps you better understand the physical demands and technical opportunities within the session. This insight allows you to tailor your practice design to better support player development. The equation considers the area size of the practice divided by the number of players [1,2].

How do I calculate it?

Length x Width = area size

Area size / number of players = relative pitch area

In this example, the practice area measures 25 metres in width and 22 metres in length, with 6 players participating. By applying the equation below, we can calculate the RPA. This value can then be cross-referenced with the RPA table to determine whether the practice area is classified as small, medium, or large.

Example:

22m x 25m = 550m2

550m2 / 6 = 92m2

RPA = Small

An example of using the pitch area dividend by the number of players to calculate the RPA.

How does this help?

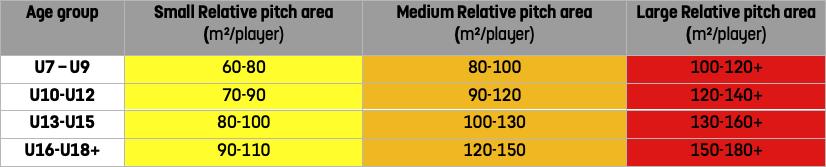

By using the following table along with your calculated RPA, you can determine whether the area is small, medium, or large for your players based on their age and stage of development. Understanding this will help you tailor the practice to achieve specific technical, tactical, physical, and psychological outcomes.

Table shows the specific ranges for small, medium and large RPA for different age groups [3]

Small

If the RPA is classified as small, players will experience technical actions under increased pressure, which may lead to fewer successful actions. A smaller RPA will require players to make quicker decisions both in and out of possession [4]. Tactically, the reduced space limits the tactical demands on players, as they have fewer options to consider. Physically, with less room to move, players will face a higher demand for accelerations, decelerations, and changes of direction. However, their total distance covered will be limited. Psychologically, a smaller pitch can help promote resilience and faster emotional recovery after mistakes, as players can more quickly influence the next action due to their proximity to the ball and opposition when a turnover occurs [5].

Large

If the RPA is classified as large, players will have more time and space, which shifts the technical, tactical, psychological, and physical demands. A larger RPA encourages match-realistic use of core skills. For example, players will have the opportunity to play both short and long passes, while a small RPA promotes shorter passes to maintain possession. Tactically, players will need support in maximising space when in possession and minimising the space when out of possession, creating a more realistic and relevant tactical challenge. Psychologically, with a larger RPA, players may experience longer periods without the ball, increasing the need for them to maintain focus [6]. Physically, players will perform fewer accelerations and decelerations compared to a small RPA, but they will cover greater distances due to the larger space available to move into or defend 7[10].

Application

If space permits, incorporating a mix of both small and large Relative Playing Areas (RPA) throughout the training week or within training sessions can help achieve different outcomes. For quick decision-making and pressure on core skills, a smaller RPA may be beneficial. On the other hand, if your practice has a tactical focus, a larger RPA can help create a more realistic and relevant experience for your players, better reflecting the demands of the game.

Coaching reflections

How can adjusting the size of the relative player area in your practice impact the technical and tactical development of your players? Are you able to provide the right balance of pressure and space to enhance their skills and decision making?

Are you incorporating both small and large RPA in your training sessions to target different player outcomes?

References

- Casamichana, D., & Castellano, J. (2010). Time-motion, heart rate, perceptual and motor behaviour demands in small-sided soccer games: Effects of pitch size. Journal of Sports Sciences, 28(15), 1615–1623.

- Castellano, J., Puente, A., Echeazarra, I., & Casamichana, D. (2015). Influence of the number of players and the relative pitch area per player on heart rate and physical demands in youth soccer. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 29(6), 1683–1691.

- Clemente, F. M., Praça, G. M., Aquino, R., Castillo, D., Raya-González, J., Rico-González, M., Afonso, J., Sarmento, H., Silva, A. F., & Ramirez-Campillo, R. (2023). Effects of pitch size on soccer players’ physiological, physical, technical, and tactical responses during small-sided games: A meta-analytical comparison. Biology of Sport, 40(1), 111–147.

- Clemente, F. M., Afonso, J., Castillo, D., et al. (2020). The effects of small-sided soccer games on tactical behavior and collective dynamics: A systematic review. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals, 134, 109710.

- Guard, A., McMillan, K., & MacFarlane, N. (2022). Influence of game format and team strategy on physical and perceptual intensity in soccer small-sided games. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(3), 1–9.

- Silva, P., Aguiar, P., Duarte, R., Davids, K., Araújo, D., & Garganta, J. (2014). Effects of pitch size and skill level on tactical behaviours of association football players during small-sided and conditioned games. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 9(5), 993–1006.

- Clemente, F. M., Martins, F. M. L., Mendes, R. S., & Silva, P. (2019). Relative pitch area plays an important role in movement pattern and intensity in recreational male football. Journal of Human Kinetics, 68, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0043